- April 23, 2015 (published in Medium)

- A piece I wrote about leaving the New York Times after working there for nine years

I’m not a fan of burying the lede, so let me just get straight to the point. I am leaving the New York Times to go work for 18F - a civic-hacking startup of sorts operating within the federal government. It is simply time to try something new. This means I am also leaving the online news business, a source of both inspiration and vexation for an unbelievable 9 years. It’s exciting, but obviously this moment is also tremendously bittersweet.

NYT kremlinologists like to inspect every departure for signs of how it is a terrible loss for the Times and an augury of how the once-venerable institution has lost its way in our modern media landscape. I’m definitely no Amy O’Leary or Aron Pilhofer, but I’ve come to see some truth within this doomsaying. Every departure is a loss, because every one of us leaves a distinctive mark on what the Times has done and continues to do every day of its existence. Nobody here is a mere cog. And yet, nobody is irreplaceable either. Being a 164-year-old newspaper means managing change while also staying the same; it’s the Ship of Theseus, but built with people instead of mere lumber.

All of which is to say, I know that I had a unique impact on the Times that will never be replicated. I was lucky to be there at the founding of the Interactive Newsroom Technologies team and a part of so many projects big and small that followed. And yet the Times will continue just fine without me, because it is an entire organization of unique talents. I have joked to friends that I probably would not be hired if I applied to work in INT today, but there is some truth to that. In the first few years I worked in a newsroom, it was disappointing to see nothing but the same faces at the NICAR conferences, even if they were all my good friends. I am thrilled at the explosion of talent that has happened in our little field these past few years, and there is no collection of news nerds as indomitable as the crew at the Times. They will continue to produce the same amazing work on deadline the world just expects them to - it looks effortless, but I can assure you that it most definitely is not - and I will continue to be surprised by their talent. That won’t change. I just won’t see the early demos first.

There are so many anecdotes I could share from my time at the Times, but I want to just pick one from back in 2006. In those days, the digital operations of the company was not integrated with the newspaper; we all reported to the business side and were housed in a building blocks away from the newsroom. But I was a troublemaker, and I wanted to work in news, dammit. So, with Derek Gottfrid as my fellow malcontent, I set up a series of meetings where I got to meet news research, computer-assisted reporting (hi Aron!) and all the other nerdier elements of the newsroom in the hopes that we might one day be able to do programming in the service of journalism. This somehow led to the ultimate cold call: a seat at the table in the kickoff meeting for the Times’ coverage of the 2008 presidential election. Halfway through the meeting, a senior editor whom I won’t name but still works in online news turned to look straight at me and asked

Why are the web people here?

I don’t remember what I said exactly. I was both defensive and annoyed, so it was probably a lot. But I can tell you the gist of it. We were failing as an organization. The Times reporters were covering only a fraction of the real election. There was a vast hidden world of data we were missing - more than votes and delegate totals - but things like campaign finance, ad spending, demographics and polling. The campaigns already knew this. We knew this. But we weren’t fixing it. We had a website, but we were still constrained by a print mentality - that the only form of a story was an article, and there was only so much space we could devote to data in the final product. But the web had changed all of that. We could capture this data, analyze it and let our readers browse it for deeper insight into the stories from the front page. The web people should be here because it was too late to not involve the web people from the start. I sat back down. The meeting moved on. But I never did.

Of course, this all seems painfully obvious today. It was likely already obvious to many of the editors in that room without me having to say it. But it’s what I needed to convince myself that what we were doing mattered as much as any story on A1. We were reporting the news too. I wanted to be a part of that. And less than a year later, the Interactive Newsroom Technologies team was formed and suddenly I was.

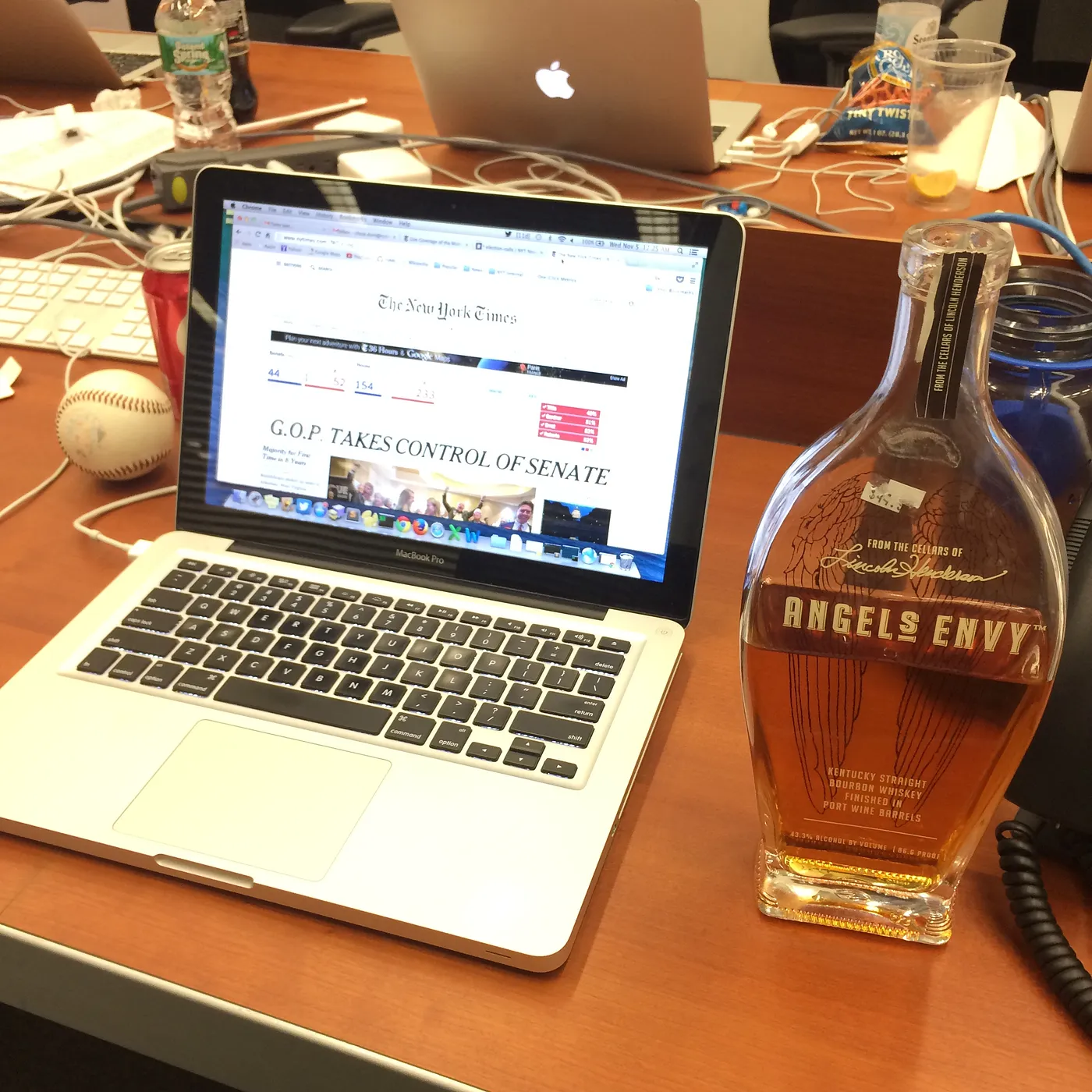

News can be a drag and news can be a drug. I wish everyone could experience what it is like to be in a newsroom on a general election night. I have enjoyed five of them in my career, and I’ve tried in vain to share on Twitter that buzz of watching history unfold from our vantage point. I remember my first time in 2008. Obama had already given his victory speech hours before, but a few of us remained in the newsroom past 3 AM sipping bourbon and watching the remaining votes trickle into the election loader. A clerk walked by and handed me a copy of that day’s newspaper, straight from the presses in College Point. My memory wants to say it was warm - like bread fresh out of the oven - even though that is absurd. But I remember looking through the newspaper, paging through to find the maps that my code had fed the data to and thinking I’m here now. Over time, the projects I have worked on will be mothballed, my friends there will move on, and the newspaper will continue making itself anew like it has all these years. No matter. Even when I am forgotten like those unknown creators of the first NYT election map in 1896, my work will survive in the archives somewhere. Nine years is a blip in the history of The New York Times, but I was a part of it. I made my mark. And for that I will be forever grateful.