This whole thing started out of spite.

In 2007, I started working at the New York Times on the digital side of operations. This was before the very new skyscraper/climbing gym had been completed, so our offices were even located in a separate building from the original New York Times’ headquarters, physically reflecting our distance from the editorial side of operations. In any event, I recall reading a piece of reporting somewhere that the NYT R&D team had built a system that could text a Times article to a person’s phone.

Well, that’s nothing fancy, I could do that, I thought to myself. I’ve since met them multiple times - and I will emphasize they have been lovely people - but there is a large part of me that hates the concept of a distinct R&D Lab in any organization because it implies there is only a specific group allowed to innovate. Yes, it’s petty and probably psychologically revealing, but this feeling made me turn to Twitter (where I already had a personal account) and register @nytimes. Then, all I had to do was write a script to do the following:

- read an RSS feed from the homepage, take all the URLs and run them through a URL-shortening service1 to make tweets

- put those into a database to keep track of what articles I’ve seen and don’t need to rescan, tweets to send (and details of those sent)

- Look for tweets that haven’t been posted yet and post 1 or 2 of them at a time.

Then, I just needed to edit my account preferences to receive those tweets as text messages and I had the NYT as messages on my phone. Voila! If you want even more technical details on the initial process, I also wrote it up in an early blog post of TimesOpen praising Twitter as “the right kind of stupid”.

The @nytimes bot officially launched on March 6, 2007

Word Up!

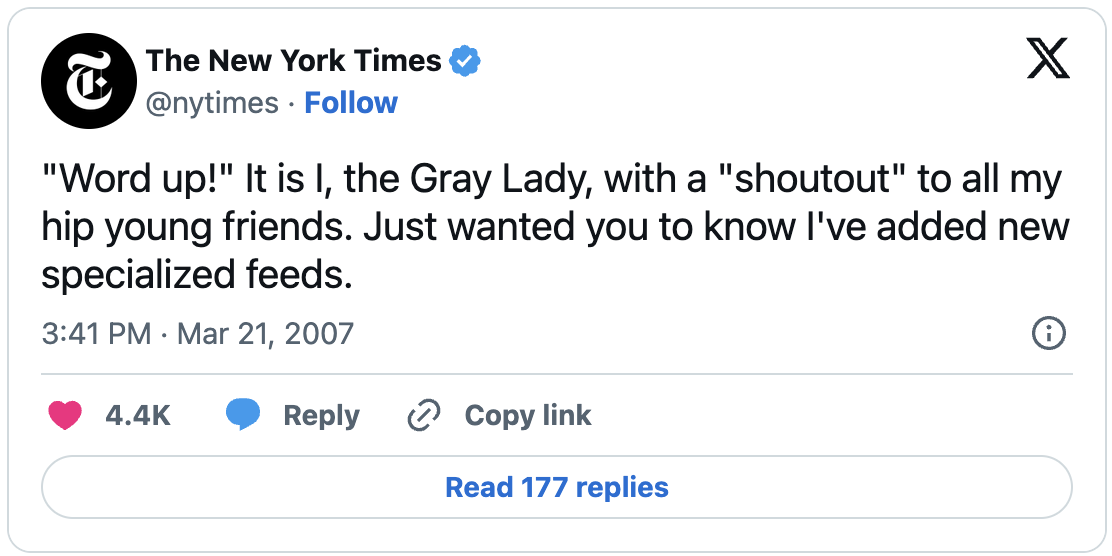

After a few weeks, I decided it would be fun to supplement the regular homepage feed by adding specialized accounts like @nyt_science, @nyt_books, etc. that used the RSS feeds from specific sections. This required some architectural revision to my original code to handle multiple accounts with different posting backlogs. I also marked the occasion with a famously silly tweet:

As I described this in an 10-year anniversary interview, the fun was “imagining what The New York Times would say if it were trying to be cool.”

“It was very important to me when I was writing that tweet that even though the metaphorical Gray Lady would try to use slang, it was still very proper grammar,” he said. “‘It is I’ versus ‘It’s me.’ It’s like the Queen trying to use slang. It had to be that combination of fusty and fashionable.”

Over the years, it’s been pretty fun to see how people have stumbled upon this tweet and wondered what had happened, but at the time only a few dozen accounts would have seen it. For the first year, the @nytimes bot was a silly hack project I just kept running, with its early user base being a weird mix of news nerds and regular nerds. In October 2017, the account finally hit 1000 followers, which felt like a huge deal at the time (but is comical considering the current follower count: 55 million)

Becoming a Product

I liked to joke that I knew the twitter feed became a product the weekend a cleaning person accidentally unplugged the machine under my desk where it was running. That morning, I rolled into work to be greeted with an email thread of people wondering which team was supporting this product, was it even an official New York Times product, do we need to get legal involved… I had to come clean and start supporting it as an official product.

I also started giving presentations to the New York Times newsroom staff explaining what twitter was and why they should consider joining it and using it for news. I especially enjoyed how I designed it to flow. Here is the third iteratio from 2009:

Around this time, Twitter also rolled out a feature called The Suggested User List, where new users could follow a group of selected account in one click so they could get an idea of what Twitter is like. They included @nytimes on the list and, as a result, the number of followers for this sleepy little accounts started increasing exponentially. What had once been a project for dozens of subscribers was now being followed by millions. Along the way, we streamlined and improved some things. The service got an actual hand-coded web admin. I moved it off my computer and into the cloud. The NYT paid for Bitly pro so we could have better short URLs. And the numbers of subscribers continued to climb.

During the height of all this, I was invited to give a talk at Twitter’s Chirp conference in 2010. The whole conference was a showcase to unveil a bunch of cool new features for developers that the company promptly reversed course on and buried unceremoniously after Evan Williams was forced out as CEO. I gave a little talk about @nytimes and how many times a NYT story is tweeted per second. I remember that for some reason the musician will.i.am was there. I also remember looking out into the audience during my section and realizing I had bored will.i.am to sleep. Good talk!

Other Bots

The @nytimes twitter account wasn’t the only Twitter bot that wrote over the ensuing years. There was something appealing about how easy it was to create silly little scripts that would feed in some content and post to Twitter. Early on in my experimentation, I made a bot that would post weather messages and change its icon based on the current weather.

After the rise in popularity of the @horse_ebooks account2 twitter account, I made my own version that would try to generate similar content from New York Times articles. The outcome was generally more weird than funny, but it did get a write-up from Nieman Lab about it.

Also, the @nytimes_ebooks code became the basis of my most famous bot, Times Haiku, details of which can be found on its own project page.

Handing Over the Keys

Eventually, the New York Times built out an entire social media team to handle strategy and content across multiple social media properties. Third party tools like buffer gave organizations the abilities to post content and track metrics easily. Hand-crafted social media content was seen as both more relatable and effective, with a higher click-through rate. Content could also be scheduled to be posted and repeated during the hours that most people were using Twitter, rather than the middle of the night when many news stories still were published (due to press times). It was time to move on. I handed over the passwords3 to the accounts into the capable hands of the NYT social media editors.

-

Originally, I used shurl, because it was slightly shorter that tinyurl (this was in the days before bit.ly). Ironically, shurl went out of business and its domain was purchased by a porn site, so I think a lot of those early tweets now link to porn. Deep sigh… ↩

-

I’m still so mad that this account turned out to be two dudes pretending to be a program. I spent days trying to figure out how they got their output so perfectly random and it turns out I was trying to reverse-engineer a Mechanical Turk ↩

-

In the days before OAuth and MFA, I was worried about someone getting access to the account to spam all our followers. I think the main account password was a 45-character random string generated by 1Password. I didn’t know. Nobody did! ↩